Finding my Prussian 5G-Grandparents at SLIG 2019 caused a huge happy dance.

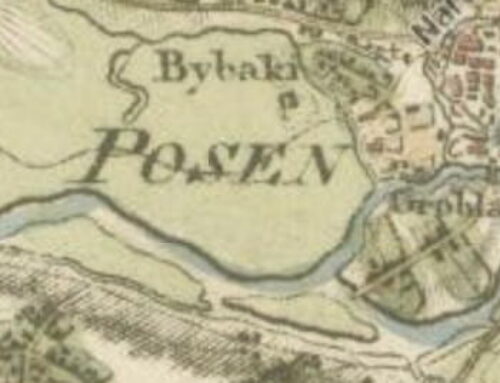

The SLIG 2019 German class taught me how to translate entries in a key German resource: the 219-volume Deutsches Geschlechterbuch, (more commonly known as the DGB). During a 2014 research trip to the Family History Library, I was thrilled to find the Schott and Kirschstein families in the DGB living in Dammer bei Namslau, Schlesien (now Namysłów, Opole, Poland).

But you know how it is: you bring your treasures home from a productive trip, cherry-pick the understandable stuff and add it to your tree. And then the rest gets placed in that teetering pile we all have called “Explore Later.”

Using Deutsches Geschlechterbuch

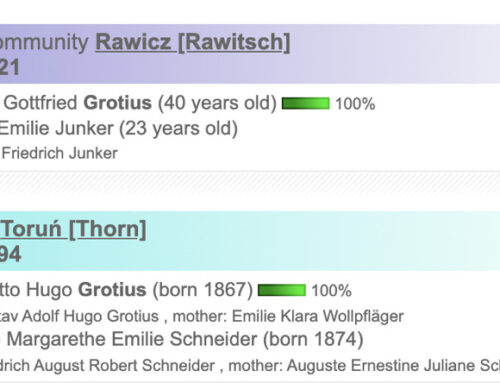

In Wednesday’s class, instructor Daniel R. Jones took the class through an entry in the Deutsches Geschlechterbuch: Genealogisches Handbuch bürgerlicher Familien. From 1889 through 2007, 219 volumes have been published, documenting the lineages of approximately 4,000 landed German-speaking families. (The closest English-language equivalent to this resource would be Burke’s Landed Gentry.)

Finding My Prussian Ancestors

Finding the Schotts and Kirschsteins in this serial publication floored me: first, because the Kirschsteins were my brickiest wall; second, because no Lutheran vital or church records survive from this part of Silesia; and third, because all and I mean all of my other ancestors were of modest means, and a significant number died in poorhouses.

Translating the Schott Entry

When I called up the scans I’d made in 2014, everything suddenly made sense. Because of the class, I now understood the special characters and symbols, the abbreviations and shortcuts, that had made much of this record inscrutable before. Here’s my translation of the record in Fraktur type seen at top:

IIb. [Deceased] Karl Siegismund Schott, [born] Dammer bei Nams-

lau . . . 1736, [died] ebd. [Latin for same [place]] 3 Dec 1791, Erbscholtisei-Besitzer

Ebd. [same place]; 2 [times married] a) . . 10 Oct 1762 with [deceased] Charlotte

Karoline Weber, [born] . . . 1743, [died] Dammer 31 Mar

1772. – b) Bodeslau bei . . . 15 Jun 1773 mit [deceased] Johanna

Elisabeth Werneke, [born] . . ., [died] . . ., daughter of deceased Elias

Werneke.Sons, at Dammer, Kr. Namslau, born,

first wife:

- Deceased Johann Gottlieb, see III c, Oldest (Dammerer) branch[additional sons and daughters cropped]

Finding New Ancestors

Karl Siegismund Schott is my mother’s mother’s father’s father’s mother’s father. (Got that? Good!) The abbreviation ebd. means the same place, so I now know he died in 1791 in the same place he was born. “Bodeslau” is a misprint for  his second wife’s birthplace. Using Meyersgaz.org, I know the village name is actually Boleslau. The gaps represented by ellipses are just that: missing facts in the lineage. I know Karl’s son Johann Gottlieb Schott (my 4-g grandfather) was his eldest child with his first wife.

his second wife’s birthplace. Using Meyersgaz.org, I know the village name is actually Boleslau. The gaps represented by ellipses are just that: missing facts in the lineage. I know Karl’s son Johann Gottlieb Schott (my 4-g grandfather) was his eldest child with his first wife.

Finding New Social Standings (Stand)

But best of all, I know Karl’s station in life. Subsequent generations of this family were Rittergutzbesitzers, or owners of a landed estate. “Erbscholtisei-Besitzer” – at first I thought this was a place he owned, but there were no place names that fit. I checked my translation again.

And finally that old reliable Google revealed an article called “Das Dominium,” by Klaus Kunze. In the 18th- and 19th-centuries, Erbscholtisei was the provincial Silesian title for the holder of a hereditary property, combined with the office of a mayor and the exercise of the lower courts….

In these early times, every Silesian village community was under a landlord; this was usually the owner of the respective manor. The manorial system and the manor were called ‘Dominium’.

The Dominium had the supervision and the right of disposal over the village green with the village road and the village pond, over the border ridges, ways, footbridges, brooks, rivers and the other undeveloped patches of the Dorfgemarkung [village district] together with special rights, their most important [of which were] the hunting right, the fishing right and the beer and spirits monopoly.

Above all, however, the Dominium within the district owned several hundred acres of land, which were managed with the help of [workers, servants, and artisans]. All landed property in the village with the exception of the manor belonged to such job owners. These ‘possessions’ were divided into three types of’ rustic sites, depending on the size and nature of the land and on the resilience of their owners: in farmers’ centers, gardener’s offices and cottages.

There’s one other thing I acquired: a #sligcold. I may not be able to finish the class tomorrow but I still have a lot to show for my #sligexperience.

It does, Steve! I’m delighted to have learned so much.

Just that discovery makes a class/trip like this worth it! It has been fun following your excursion; thanks for sharing.