In the New York Times today, an interesting article by Bess Lovejoy and Allison C. Meier on the graves of forgotten New Yorkers.

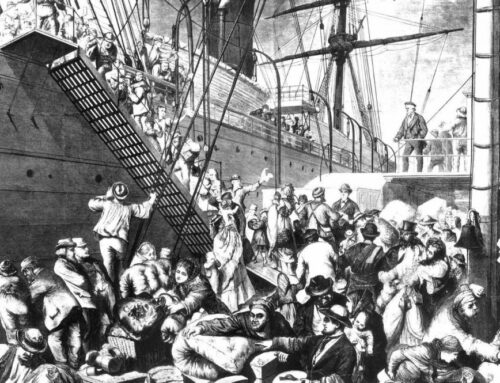

Believed to be the largest and most active potter’s field in the country, Hart Island has accepted New York’s dead since the mid-19th century.

At least one million souls – the homeless, the poor, the stillborn, the unidentified and the unclaimed – are buried there. In its long history, however, access to the island of forgotten New Yorkers was either forbidden or greatly restricted.

The history of the Hart Island potter’s field is one of fear and isolation.

At one point, Manhattan was home to about a hundred graveyards. But during the 19th century, rising real estate values and fears that decomposing cadavers were producing an unhealthful “miasma” prompted New Yorkers to move their dead out to Brooklyn, Queens and beyond. Of course, some of New York’s dead were never buried in the heart of town: The earliest black residents were interred outside the boundaries of the New Amsterdam settlement, near today’s African Burial Ground National Monument in Lower Manhattan. Then, as now, the hierarchies of the dead reflected the hierarchies of the living. Today that hierarchy continues on Hart Island, where the city’s poorest are laid to rest by criminals — the untouchables burying the untouchables.

This may have once made some sense. In the years after the city bought Hart Island in 1868, the Department of Public Charities and Correction operated an asylum and a workhouse there. But these days, the burials are the island’s only operation. Security concerns, in part prompted by the inmates who work there, stigmatize visitors. The prohibition against grieving families’ visiting graves and the requirement that they hand over cameras and phones even on closure visits have made mourners feel like prisoners themselves.

Read the full text of The Graves of Forgotten New Yorkers and the proposal to make the island more accessible.

Leave a Reply