What were immigrant inspections

at Ellis Island and other U.S. ports like for your ancestors?

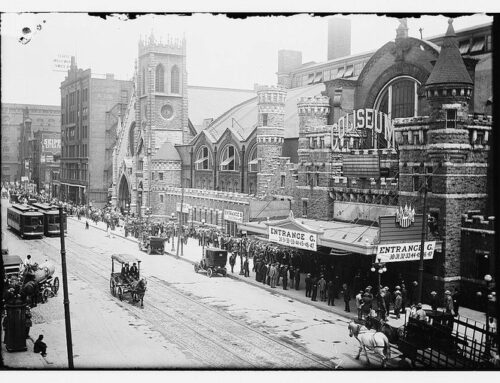

Best known of all immigrant arrival ports in the U.S., Ellis Island operated for just over 60 years. Most immigrants entered the United States through New York Harbor via the great steamship companies like Hamburg-America (HAPAG), White Star, Red Star, and Cunard. Others arrived in ports such as Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, San Francisco, Savannah, Miami, and New Orleans. Late-19th- and early 20th-century inspections were common experiences regardless of port. If you are unsure about which port your ancestors came through in the U.S., check out my post on available passenger lists and links for all U.S. ports.

Here are the immigrant inspections at Ellis Island and other U.S. ports:

Disembarking Inspection

Ticket class affected not just the voyage, but also how passengers came ashore. Incoming ships anchored in a designated quarantine area at the Narrows, the entrance to New York harbor.

Ticket class affected not just the voyage, but also how passengers came ashore. Incoming ships anchored in a designated quarantine area at the Narrows, the entrance to New York harbor.

Health officers boarded and examined the ship for signs of contagious disease, including cholera, plague, smallpox, typhoid fever, yellow fever, scarlet fever, measles, and diphtheria. First- and second-class foreign passengers were briefly examined at this time; U.S. citizens were exempt from review. After clearing a ship, health officers returned by cutter to Ellis Island. Ships then sailed into New York harbor and first- and second-class passengers disembarked.

Smaller barges transferred steerage passengers to Ellis Island. The new arrivals were issued ID tags, with their names, a number for ship’s manifest, and a page number for their names on the manifest. Pinned to their clothing, the tags contained instructions on the back translated into 10 languages, including Yiddish.

Medical Inspection (“The Six-Second Medical Exam”)

Unwittingly, all immigrants faced their first test when they walked over to and climbed the stairs to the Registry Room. As the new arrivals walked up, officers from the United States Public Health Service observed them. Journalist Frederick Haskin, in his 1917 book, The Immigrant: An Asset and a Liability, wrote:

While the immigrant has been walking the twenty feet the doctors have asked and answered in their own mind several hundred questions. … If he is so evidently a healthy person that the examination reveals no reason why he should be held, he is passed on. But if there is the least suspicion in the minds of the doctors that there is anything at all wrong with him, a chalk mark is placed upon the lapel of his coat.

According to some oral histories, more experienced immigrants counseled fellow travelers to reverse their clothing if they had been marked, to avoid additional examinations and possible deportation. Known among staff as the “six-second medical exam,” the stairs and inspection were a quick way to assess the need for further physical examination.

Those selected were separated by gender for examinations in groups. Immigrants were detained if suspected of a “loath-some or a dangerous contagious disease,” and, after 1907, immigration legislation placed special emphasis on “those likely to become a public charge,” or LPCs.

Legal Inspection (“Pocket Examination”)

Family groups were called for immigrant inspections to demonstrate their economic and moral fitness to inspectors.

Family groups were called for immigrant inspections to demonstrate their economic and moral fitness to inspectors.

No matter what your great-uncle told you, inspectors at Ellis Island did not change your family name. The inspector, sometimes assisted by a translator, usually spent about two minutes per person, checking answers against the ship’s manifest to basic questions about nationality, marital status, and occupation.

Additional questions or tests depended upon prevailing immigration law. Immigrants called this stage “pocket examination” because of the need to show funds and paperwork.

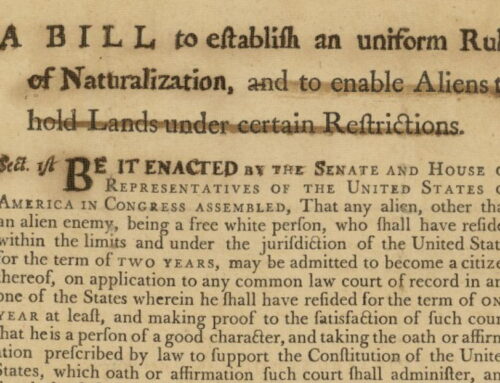

From the 1880s, anti-immigration groups had tried to impose a literacy test to restrict immigration. The Immigration Act of 1917, passed over President Woodrow Wilson’s veto, required all immigrants, 16 years or older, to be able to read a 40-word passage, usually Biblical, in their native language. Medical inspections of all immigrants were also made mandatory in this legislation.

Immigrants requiring additional review were marked SI for Special Inquiry along with specific codes for legal or medical reasons. Immigrants then encountered an extended interview, additional physical and mental testing, and review of paperwork with inspectors.

Physical, mental and legal immigrant inspections at Ellis Island were grueling at the end of a long voyage in steerage.

Have you found records of your ancestors being

detained at Ellis Island for special inquiry?

Have you found ancestors requiring additional immigrant inspections documented on records called Records of Aliens Held for Special Inquiry? Read about their experiences here.

Discovering Immigrant Ancestors Guide

For more information on the immigrant process of your ancestors, from the time they left their European villages until they settled in their new homes, try Discovering Immigrant Ancestors, a Sassy Jane Genealogy Guide.

The “Finding Migration Records” chapter has 25 pages of active links for essential and lesser-known resources for departure, arrival, migration, passenger lists, and naturalization records. The focus of this chapter is on finding records for the second and third waves of migration from Europe to the United States, between 1865-1920.

Do you know what the abbreviation “PGT” means on the manifest of a detained female immigrant? Could it be “pregnant”? She was 23 and also designated “LPC”, then deported back to Spain within 4 days of arrival in 1911-12.

Your guess is correct that PGT meant she was pregnant.

Thank you. This was an extremely informative article. Looking at this process from the immigrant’s view, I’ve often wondered about other aspects, such as, sanitary conditions, sleeping conditions, food, and length of their stay.

Thanks, Eileen. I think it was quite grueling, especially after long journeys in steerage. Stay tuned for another post on this soon.