The world pauses today for International Holocaust Remembrance Day 2020. This date also marks the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau by the Red Army.

It seems too little just to read the accounts of survivors, who have returned to this fraught place on this momentous day. And yet looking at their faces as they come together saying, NEVER AGAIN, a whole world of pain, suffering, loss, and survival is revealed.

The image at top features Dora Bornstein carryingher five-year-old grandson Michael out of Auschwitz in late January 1945 (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland). Let’s learn more about the Bornstein family.

The Power of Family

Survivor Michael Bornstein plans to bring the totemic family Kiddush cup to Auschwitz today. Overcoming his reluctance in 2017, Bornstein  recounted his survival story with his daughter in Survivors Club: The True Story of a Very Young Prisoner of Auschwitz. Daughter Debbie describes it as the most important work of her professional life.

recounted his survival story with his daughter in Survivors Club: The True Story of a Very Young Prisoner of Auschwitz. Daughter Debbie describes it as the most important work of her professional life.

Born in 1940, Michael was the son of an accountant and homemaker. He and his family were among 3,000 Jews living in Nazi-occupied Żarki, a medieval Polish town where Jews had lived for centuries. He arrived at the Birkenau train entrance on a hot summer afternoon in 1944 with his mother, Sophie; his father, Israel; 8-year-old brother, Samuel; and grandmother, Dora.

Today, Michael remains one of the youngest survivors of the Holocaust, sent to Auschwitz when he was only 4. Of the 2,819 Auschwitz prisoners freed by the Russian Army on 27 Jan 1945, only 52 were under the age of 8; Michael was one of them. “It was just unbelievable,” Bornstein recalled. “The normal lifespan of a child my age [in the camp] was about two weeks. And I managed to survive in Auschwitz for about seven months.”

Upon liberation, Michael recalls the Soviets treated them

like humans…. Offering real pillows and real food, even chocolates and cookies. We showed them our tattoos to identify ourselves, but they pushed our arms aside and asked for our names. We weren’t prisoners anymore—we were survivors. We weren’t numbers anymore—we were people.”

I am Michael, I told the soldiers.

After the War

In the town of Żarki, fewer than 30 Jews returned—and almost all of them were from Michael’s Jonisch or Bornstein families. But they were dispossessed, real estate and cached goods appropriated by Polish neighbors, except for that single Kiddush cup.

Michael was reunited with his mother, who applied for visas to the United States. In an account to his alma mater, Michael recalled his mother

….said the word “America” the way a child says the word “candy.” She told me America was the most wonderful and welcoming place you can imagine.

Dora decided to stay in Poland. After his survival against all odds, Bornstein resisted family attempts to learn of his experiences during the Holocaust. His daughter recalled this reluctance: “I would ask my dad, ‘What was Auschwitz like? What was it like to be in a concentration camp? And his answer was usually, ‘Oh, Debbela, ‘I don’t remember. Why do you why want to talk about terrible things?’ But with survivors dying, and his grandchildren growing up, Bornstein decided it was time to fully understand and tell his story.”

Of this book, The New York Times review notes:

So many other remarkable stories must lie in hiding, waiting to be shared with the world. The Bornsteins’ important work provides an inspiring reminder: What could be more rewarding than capturing and preserving family history? Perhaps the experience of creating a true historical archive — together.

What Can Genealogists Do?

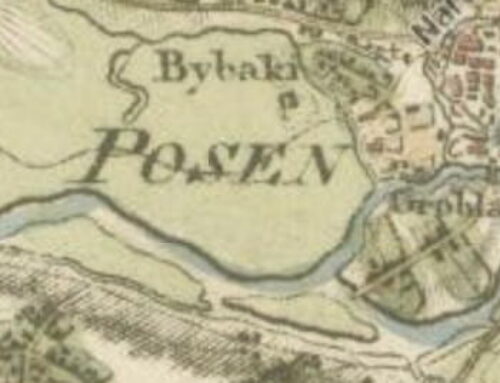

I admit I feel powerless to describe and acknowledge this suffering, persecution, and death. The Prussian side of my family comes from this disputed area between Germany and Poland. And, while my DNA does not reveal a Jewish link, the historian in me wants to testify to this mass murder and suffering. If my relatives had not left in the 1880s, what would their role have been in their villages as Lutherans?

As genealogists, let us pledge to:

- Acknowledge the depth of suffering in the Holocaust by reading and understanding

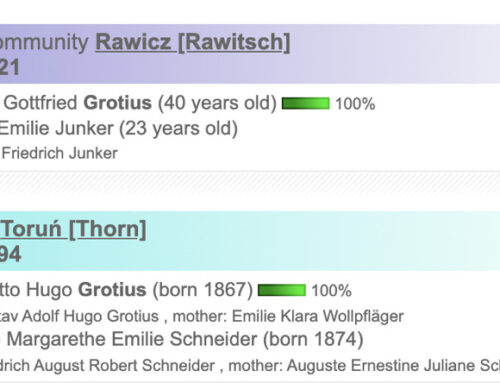

- Support fellow Jewish genealogists in their Holocaust research

- Encourage new avenues of Jewish research, both in Holocaust and other records.

Great column! The more it’s put out there, the more it will be properly remembered. It just baffles me as to how anyone can claim this never happened. And, I, like you, have many German ancestors. I have often wondered what those who lived during the Nazi period thought at the time. I just don’t know how

I would react if I found actual evidence of any of my ancestors taking any part in this horrific event.

Thx, Loyal Reader. I admit when I started researching my German Lutherans, I was filled with dread at what I might find. Happily, they all left in the 1880s. As it turns out, my Germans were all Prussians. My German-speaking Lutherans who stayed in Prussia were affluent; they were dispossessed at the end of World War I. But they escaped with their lives in 1919, unlike their Jewish neighbors from 1933-1945. There’s a blog post in there, but I seem to have written it in the comments. :)