At certain times in the early 20th century, women lost U.S. citizenship when marrying foreign-born men.

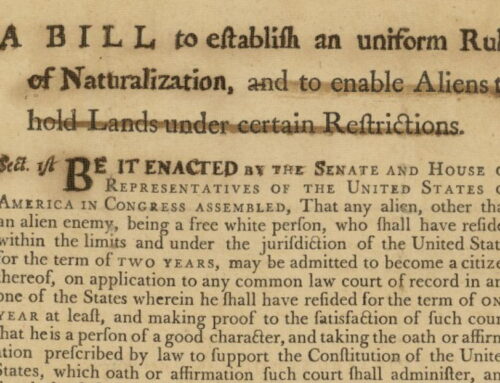

The U.S. Expatriation Act of 1907 mandated that all women acquired their husband’s nationality upon marriage. As a result, American women who married foreign-born men in the United States between 1907 and 1922 lost their U.S. citizenship.

Before 1907, women who married foreign-born men and continued to live in the United States remained American citizens. After March 2, 1907, provisions of the Expatriation Act changed all this. Congress mandated that “any American woman who marries a foreigner shall take the nationality of her husband.” Therefore, after 1907, regardless of where the couple resided, the woman’s citizenship was determined solely by her husband’s.

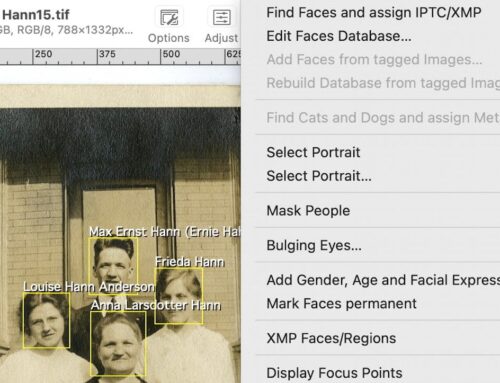

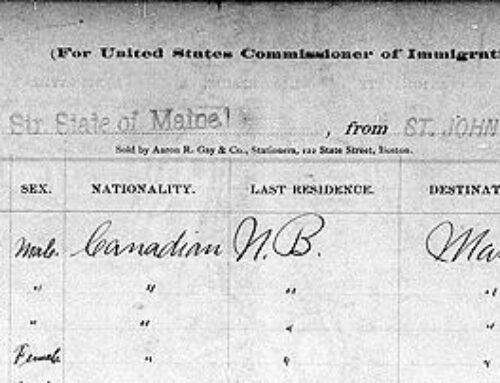

I had heard of this anomaly when I researched naturalization records for my e-book, Discovering Immigrant Ancestors. But I only realized recently that my great-aunt, Louise Marie Hann, found herself exactly in this situation when she married Swedish-born Ernest Anderson in Chicago in 1913. (They were married by his brother, Erik, a pastor.)

Suffragists who had won the hard-fought battle for voting rights for women in 1920, sometimes discovered they were still disqualified because of their husbands’ nationalities. Urged on by these women’s rights activists, Ohio Congressman John L. Cable sponsored legislation to give American women “equal nationality and citizenship rights” as men. The Cable Act of 1922 resolved the situation for couples marrying in or after that year. However, the Cable Act perpetuated the loss of citizenship for American women who married “aliens ineligible to citizenship,” namely Asians.

Meg Hacker’s article, “When Saying “I Do” Meant Giving Up Your U.S. Citizenship,” explains:

If a (former) American woman’s alien husband became a naturalized U.S. citizen after the marriage, she would regain her citizenship through the very husband with whom she had lost it. If the same woman wanted her American citizenship restored, and her husband had not naturalized, she had to go through the entire naturalization process as a true immigrant, with all of its standard rules and regulations. Even then, she was still tethered to her husband through his political or legal standing. If the United States, for whatever reason, would not grant him citizenship, it would not extend any repatriation opportunities to his wife.

But what about women who had already lost their citizenship—what could they do? They would still have to follow the full standard naturalization process. The Cable Act’s restrictions caused some confusion. A wife’s citizenship status no longer changed automatically upon the husband’s naturalization—in fact, it did not change at all. Some women who had married before passage of the act understandably believed they had either never lost their citizenship in the first place or assumed that they held the same status as their husbands (and, no doubt, children). After 1922, women who thought they had lost citizenship by marriages due to the 1907 act had to file a petition for naturalization if they wished to regain it.

During my genealogical research, I discovered that Great-Aunt Louise only regained her citizenship when her husband was naturalized in 1924. Ironically, her second sponsor for citizenship was my Norwegian-born great-grandmother, who gained citizenship when her husband was naturalized.

To learn more about Women in naturalization records, go to www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1998/summer/.

This occurred in the UK, too. I was researching a friend’s family and discovered that this had happened to one of his relatives. I wrote a blog post about it, and it attracted some interesting comments from people with stories from their own families. http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/do-you-take-this-man-and-his-nationality/

Thanks, Audrey, for the new information re the UK. Appreciated!

A query. My young single GM emigrated in 1907 to New York.

In 1913 she married a immigrant to Canada who would by then be considered a Canadian. From 1913 to 1917 they lived in NYC. During that period, her father sought and obtained Naturalization for all his family including his married daughter (my GM). This was obtained in Nov 1917.

Is it correct to understand that by this 1917 legal action, she became a US citizen?

PS. by GM and GF shortly thereafter emigrated to Toronto, Canada.

No, I don’t think that’s correct. Once your grandmother married, her father’s status would not determine hers, I wouldn’t think. (Unless her father was naturalized before she married, of course, but that doesn’t sound like the case. Did your grandmother marry in the U.S. or Canada? What do census records say about her nationality?

What about children born of an alien, non-naturalized man and a U.S. citizen wife? What was their status?

Hi Bonnie! This legislation obviously caused lots of confusion and I think this is one example. When I look at my great-aunt’s family group, she married in 1913, losing her citizenship. Her three children were born between between 1918 and 1922 in Chicago, so I believe they are covered under jus soli, or birthright citizenship.

Birthright citizenship (back in the news as a campaign issue, bizarrely enough) is “a legal right to citizenship for all children born in a country’s territory, regardless of parentage.” So Great-Aunt Lou’s children gained/retained their U.S. citizenship by birthright while their mother forfeited hers by marriage.

I am led to think that my great-uncle and -aunt were completely unaware that this legislation applied to her, thus the late 1927 application for her naturalization. What a tangled web this 1907 law caused!